• • •

"Mike and Jon, Jon and Mike—I've known them both for years, and, clearly, one of them is very funny. As for the other: truly one of the great hangers-on of our time."—Steve Bodow, head writer, The Daily Show

•

"Who can really judge what's funny? If humor is a subjective medium, then can there be something that is really and truly hilarious? Me. This book."—Daniel Handler, author, Adverbs, and personal representative of Lemony Snicket

•

"The good news: I thought Our Kampf was consistently hilarious. The bad news: I’m the guy who wrote Monkeybone."—Sam Hamm, screenwriter, Batman, Batman Returns, and Homecoming

March 10, 2011

The Energy Talk, part 3

By: Aaron Datesman

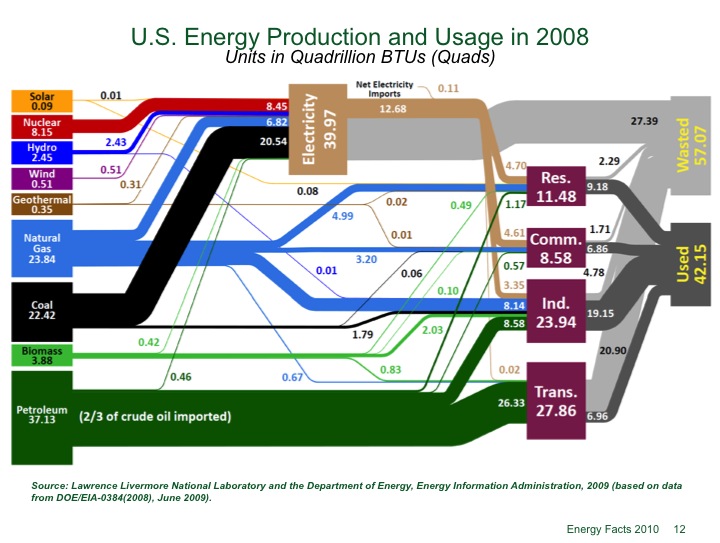

Having learned a little bit about energy supplies and demand sectors, I think this slide from Dr. Dehmer’s talk is my favorite. It describes how energy supplies match to sectors, and also includes a noteworthy lesson about thermodynamics. It differs from the previous slide in that Electricity is broken out as a separate sector. That is why, you’ll note, the four sectors (Residential, Commercial, Industrial, and Transportation), together with the waste heat from generation of Electricity, sum to 100 Quads.

(credit to Dr. Patricia Dehmer, DOE-SC)

Broken out in this way, the Transportation sector is a larger consumer of energy than the Industrial sector. This is contrary to the information on the previous slide. However, there is no fundamental contradiction. It’s just a matter of accounting, to decide whether the waste heat from Electrical generation powering Industrial processes belongs in the Industrial sector or in its own stream.

Going back to Part One, you may have noticed that electrical generation creates both waste heat and useful energy at a ratio of about 2:1. (In that example, it’s 62:38 = 1.6; in the graph above, it’s 27.39:12.68 = 2.2.) This observation is fundamental to any basic discussion of energy supply and consumption: of the energy available from fossil sources, we lose about 2Watts in heat for every 1Watt we generate in useful electrical power. The limiting physical rule which describes how this works is called the Carnot cycle.

The Carnot cycle applies to the operation of “heat engines”, so there are very strong limits to the efficiency for all generation technologies based on combustion – including automobiles. The only way around the Carnot cycle limitations (which derive from the physical law that entropy never spontaneously decreases) is to make time run backwards. So, we should get to work on that.

Having discussed the significance of waste heat, the real message of this slide is obvious: of the primary energy sources employed by the economy, we waste more (57 Quads) than we use (42 Quads). Huh.

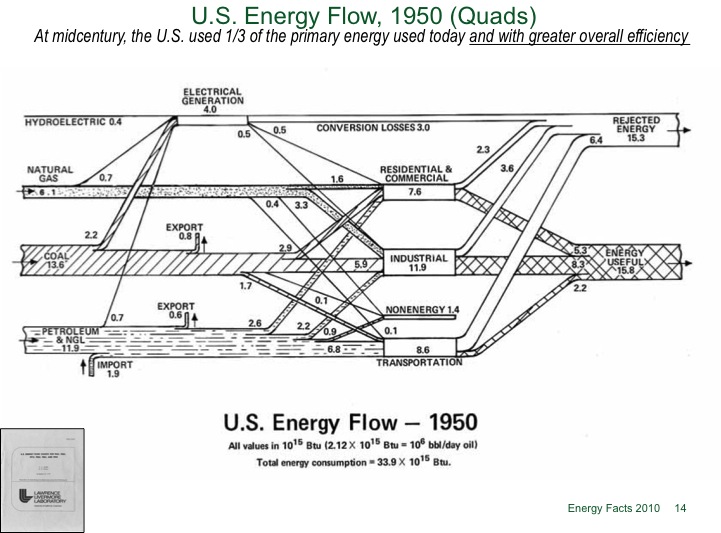

This does not fundamentally mean that we’re irresponsible users of energy. The limits imposed by basic physics are hard limits. However, the equivalent information, circa 1950, is highly illuminating.

(credit to Dr. Patricia Dehmer, DOE-SC)

In 1950, the U.S. economy relied upon 15.8 Quads of useful energy while generating 15.3 Quads of waste heat – a bit better than a 1:1 ratio. Apparently the overall energy efficiency of the U.S. economy has DECREASED quite a bit over the last 61 years.

I suspect the story here is that we now use a lot more energy (normalized to the overall usage) in applications which waste a lot – specifically, home refrigeration, air conditioning, and automobile miles. If anybody would like to read the source document (EIA-0384) to verify or refute this hypothesis, I would welcome the help.

BONUS: If you look at the 2008 chart and calculate the efficiencies by sector, you might reach an interesting conclusion about how the Livermore scientists developed the numbers presented. I leave it to the reader to decide whether he or she is actually that bored.

DOUBLE BONUS: It might be more interesting to watch Dr. Dehmer present her talk herself, rather than read me consistently incorrectly portray the important points in the wrong order. The link doesn’t work for me, but a video from 2006 seems to be available here.

— Aaron Datesman

about bonus question #1, i'm sure those were the best possible approximations available with their limited technology at the time.

Posted by: hapa at March 10, 2011 11:32 PMInteresting point indeed. The residential, commercial, and industrial sectors all show efficiencies of 80% in 2008 and 70% in 1950. Both the transportation sectors shows an efficiency of 25% which I've heard quoted as the efficiency of an automobile's internal combustion engine. Notably the efficiency of electrical production rises from 30% to 31.72%.

As someone who has received some science training, I was uncomfortable with the data in the presentation due to the lack of uncertainties but disregarded my concern due to the apparent lay nature of it. In my opinion uncertainties should not be omitted in lay discussions but rather have their significance explained. After reviewing this result, I am even more uncomfortable now. I can accept limitation in the precision of data but to present data in a way that masks a lack of precision as is done here (it suggests a .005% uncertainty in the efficiency of the sectors when it is more likely to be more then 5%) is dishonest and doesn't serve Dr. Dehmer well. This is especially true for people who don't have the science training that I have.

Taking a 5% uncertainty in the efficiencies of all sectors: in 1950 the US wasted 15.3+/-.8 quad of energy while it consumed 15.8+/-.8 quad of energy for an overall efficiency of 50.8+/-1.9% whereas in 2008 the US wasted 62+/-3quad of energy while consuming 40+/-3quad of energy for an overall efficiency of 39.2+/-2.0%. This yields a chi squared that the numbers are the same of about 4.25 (with one degree of freedom) which means that there is less then a 4% chance that the 2009 was more efficient then 2050.

The analysis is hampered by the fact that the numbers don't add up in the 2009 example. In 2009 the US generated 39.97 quad of electricity of which 12.68 quad was consumed and 27.39 quad was wasted. The sum of the consumed and wasted generated electricity was 40.07 quad. While I haven't checked the whole thing I suspect there are other discrepancies. This further reinforces the irresponsibility of reporting these numbers to 4 figures.

I only took into account uncertainties in the efficiency estimates and a rather low uncertainty at that. Using a 10% uncertainty the chi squared roughly halves leaving a 15% that 2009 was more efficient then 1950 which isn't strong enough for a scientific conclusion. Despite the numerous problems in the analysis given, one can reasonably claim that the US was more energy efficient in 1950 then it was in 2009 based on the presentation given but it is not a claim I would make based it. It is a reasonable conclusion for the reason Mr. Datesman explained: a higher portion of energy is in the form of electricity in 2009 then in 1950. This would be due to the ease of use of electricity.

I have another interesting point that I found while doing the error analysis. Between 1950 and 2009 energy consumption rose in residences and commerce 50%, industry 110%, and in transportation 220% (since I didn't assume any uncertainties I didn't use any and am using a significant figures system). I think it's clear where the problem is if we are consuming too much energy per capita.

In any event I have to question the precision of the data presented throughout the presentation. Since the precision was presented dishonestly I also have the question the accuracy (which has shown it's own independent problems) and even the general honesty of the presentation. This also speaks to the broader issue of public faith in the scientific community as I fear this presentation may be misleading in the details and that doesn't serve the problem of public perception of science. Hopefully Dr. Dehmer addressed these concerns in her presentation although I'm not sure if I can find time to watch a 20 hour presentation. I'm also not surprised but concerned that the University of Maryland doesn't provide a written transcript.

Posted by: Benjamin Arthur Schwab at March 11, 2011 01:23 AMthese maps also don't tell us whether the machines involved are using the energy well. there's no distinction between a prius and a hummer, for instance. per gallon the two would be very similar?

the maps may not mean we're irresponsible users of fossil energy, but they do show why plans to defossilate the grid involve building far less supply than is being replaced: there's no need to replace the losses in generation.

Posted by: hapa at March 11, 2011 01:43 AMPer gallon I doubt a Prius and Hummmer would get similar mileage. Assuming the difference is real (because not going to spend time to discover otherwise) I can think a pair of possible explanations - less electric heating and more train traffic.

Electric heating is not the predominant form of heating even today - always been more expensive than alternatives (leave aside heat pumps for heating - too small market penetration to count in this discussion). But electric heating was MUCH less common in 50's than today. So that would make a difference.

Auto was already a pretty dominant form of passenger transport for day to day use (though not not as common as today we will get to that.) But trains carried a much larger share of long-haul freight than today. There was twice as much heavy rail track as today, competing with many fewer trucks. Long haul trucking carried a MUCH smaller share of ton-miles than today. Since a freight train spends 1/20th of the fuel to carry a ton of freight one mile (and about 1/18th after taking less direct routes into consideration) that is a huge savings. Similarly long distance travel by train was much more common than today. Multi-day driving trips and flying were both rarer. Trains carried a lot of people long distances who would drive or fly today.

Lastly even when we talk shorter trips, though autos were already dominant, trains carried a larger much larger share than today. Even the dismantling of streetcars, though mostly complete, was not quite finished.

So - more direct fueling of space and hot water heating ,less use of electricity for that purpose (as a share of total not just in absolute numbers). Freight carried much more by rail. Passenger rail also had a bigger modal share than today. A higher percent of population who did not own cars. If the difference is as stated, those things would explain it.

Posted by: Gar Lipow at March 11, 2011 02:43 AMno i meant when it comes to actually burning a gallon of gas, however far each vehicle travels on that gallon, the energy lost in the combustion is similar, so they're treated as equal performers in the eyes of these chart. they aren't about finding different ways to do the thing.

Posted by: hapa at March 11, 2011 05:33 AMAaron

I'd be interested in more data as to how the utility/waste ratio changed over time, perhaps data showing how the ratio changed each decade. Then I think we'd get a better basis for speculation, though your speculation seemed pretty good to me. (Another approach would be to understand the damn math, which I can't do.)

Anyway, here'a link on the changes in the electrical engineering world starting as of about 1950, before air conditioning became a right and night in places like Nevada became neon:

http://ecmweb.com/mag/electric_12/

Posted by: N E at March 11, 2011 07:54 AMBAS - points about error are always worthwhile, but remember that all you are looking at is one slide (or a couple of slides) representing a lengthy report. Before you break out your statistical tools, why don't you follow the reference provided on the slide? Go read the EIA report. It would be a better use of everyone's time than it is to call a very prominent scientist dishonest based on one summary slide. That rubs me the wrong way, to be very frank.

Step back and look at the real message here from the perspective of a general audience. How many Americans know that the 20 Watt light they left on in the kitchen is wasting an additional 1000 Watts of heat power from primary energy sources? (Maybe the number is 100 Watts. Or 50 Watts. Same question.)

Frankly, since I've seen these slides, I've been much more conscientious about turning off lights in my house. The rest of it is all detail - it deserves to be critiqued, but it's detail.

About the 1950 vs. 2009 comparison, since you have some science training, you should understand that the growth of air conditioning and refrigeration are major contributors to the growth of the waste heat burden, since these technologies utilize heat engines run in reverse cycles.

Teasing out whether this contribution is bigger than the growth of transportation is an interesting exercise, but not one that I have time for.

I appreciate the comments, and please call me Aaron. Nobody has called me Mr. Datesman since before I deserved it.

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at March 11, 2011 11:51 AMbtw i hadn't realized the extent to which natural gas was being used for process heat, or that coal-fired power is more than 90% of its use.

Posted by: hapa at March 11, 2011 12:47 PMAaron,

These are definitely the most interesting of the "Energy Talk" diagrams thus far.

I would have to examine the raw data more closely, but there's something fishy about the quoted efficiency (~25%) for the 2009 transportation sector. That exceeds the typical operating efficiency (~20%) of internal combustion engines, even without considering losses such as air drag. Moreover, virtually all of the kinetic energy developed by vehicles is ultimately 'wasted' as heat when the brakes are applied (except in a very small fraction of newer electric/hybrid vehicles, where some of this energy is recovered).

Posted by: SunMesa at March 11, 2011 12:50 PMMoreover, virtually all of the kinetic energy developed by vehicles is ultimately 'wasted' as heat when the brakes are applied

Plus they're probably just out on a nacho run.

Posted by: saurabh at March 11, 2011 01:43 PMSunMesa,

Gar Lipow made this point in another thread, but a great deal of transportation involves trains carrying freight - and they are much more efficient than passenger automobiles. As I wrote to BAS, I bet that document from the Energy Information Administration would make really interesting reading.

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at March 11, 2011 02:20 PMA ton of the increase in waste comes from the increase in electricity use. That's a very small electricity slice in 1950, and electric generation is inevitably going to lose a ton (heat losses in generation + transmission losses + inefficiencies on site).

Posted by: RobK at March 11, 2011 02:36 PMAaron,

Gar Lipow made this point in another thread, but a great deal of transportation involves trains carrying freight - and they are much more efficient than passenger automobiles.

However, as Gar noted upstream in this thread, a larger fraction of freight was carried by train (vs. by truck) in 1950 than in 2009. And yet, the efficiencies in the transportation sector for these two periods are virtually identical (and excessively large, IMO, per my previous post).

I'm having trouble finding the specific EIA reference cited in the graphic, but a more recent version of the equivalent data can be found at:

http://www.eia.doe.gov/aer/pdf/aer.pdf

Rob, I'm sure your right that increased electricity use is part of it. But I'll bet air conditioning and refrigeration does not play as large a role as Aaron suggests. Reason: Coefficient of Performance. Refrigerators and air conditioners are both heat pumps. They move heat around. They don't generate heat or cold directly. So it takes less than a unit of electricity to move a unit of heat. And that COP is higher for cooling than heating. (Reason heat pumps are less common for heating than air conditioning and refrigeration.) So say power loss during generation and transmission and distribution is 70%. So the total heat value of the electricity at your plug is 30% of the fossil fuel that generated. If that electricity runs an air conditioner with an average COP of 2, then the "coolth" generated is about 60% of the heat value of the fossil fuel burned. Which is why cooling and refrigeration will increase electricity usage but not lower efficiency the way the slides define efficiency. (If anyone reading this starts muttering anything about thermodynamics to yourself, please Google "Coefficient of Performance" before you post. )

Posted by: Gar Lipow at March 12, 2011 02:18 AMFun thread - this definitely enhanced my understanding of the diagrams. Thanks everybody!

Gar, thanks for pointing out the error in my thinking. I used to work in cryogenics and am accustomed to thinking of all of the heat dumped at the hot reservoir as waste heat. That isn't actually correct - heat drawn from the cold reservoir represents useful work if cooling is the point of the exercise.

I think this is the link to the actual report: http://www.eia.doe.gov/aer/pdf/aer.pdf

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at March 12, 2011 10:48 AMWhich SunMesa already said..... sorry....

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at March 12, 2011 10:54 AMAnd on page 56, as I suspected the share of electricity used for heating is way up from 1950. That alone is a huge efficiency drop. Resistance heating is probably the single least efficiency use of electricity (at least of routine uses). That applies to space and hot water heating, and to electric stove tops as well.

Posted by: Gar Lipow at March 12, 2011 04:08 PMGar and Aaron

I get the distinct impression, despite not understanding most of what you say, that you guys really know what you're talking about. I had the same impression of Professor Chazelle when he got going on Bach or music generally. Muchas gracias.

Posted by: N E at March 13, 2011 02:41 AM