• • •

"Mike and Jon, Jon and Mike—I've known them both for years, and, clearly, one of them is very funny. As for the other: truly one of the great hangers-on of our time."—Steve Bodow, head writer, The Daily Show

•

"Who can really judge what's funny? If humor is a subjective medium, then can there be something that is really and truly hilarious? Me. This book."—Daniel Handler, author, Adverbs, and personal representative of Lemony Snicket

•

"The good news: I thought Our Kampf was consistently hilarious. The bad news: I’m the guy who wrote Monkeybone."—Sam Hamm, screenwriter, Batman, Batman Returns, and Homecoming

April 04, 2011

Not A Super Model

We’ve all done the problem in high school physics with the cannon and the muzzle velocity and the launch angle, where the teacher asked us to find the range of the projectile. It’s standard. It’s also standard to begin the problem statement with the qualification, “Neglecting air friction….” If the cannon is a rocket and you took the class in college, perhaps you were told to neglect the rotation of the earth as well. There’s nothing remarkable about this.

It’s a somewhat simplistic example, but what I’ve just described is a powerful mode of physical reasoning employing a model. We can’t solve the actual scenario where the wind is blowing at different speeds at different heights, the air friction is a complicated function of velocity, and the earth is spinning – in fact, most of those parameters cannot be known explicitly and can’t be stated. So we invent a simplified, model problem which we can solve exactly, in the expectation that the answer will be sufficiently close to real life to be useful.

The use of models to address research questions is often unstated; but, once you have trained yourself to look for them, they are completely ubiquitous in all fields of science and engineering. When the model assumptions are justified, the technique represents a sublime application of human intellect. When the model assumptions are unrecognized or unexamined, however, GIGO is the operative rule: Garbage In, Garbage Out.

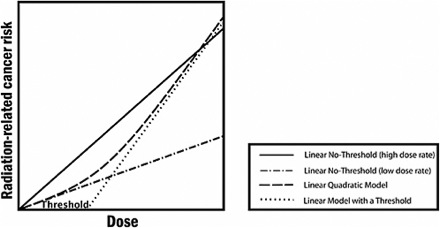

Since the Fukushima disaster began to unfold, I have been thinking a lot about an important model with a GIGO outcome: the Linear Dose Model (and its variants, including the Linear No-Threshold Model). The LDM relates dose of energy absorbed from ionizing radiation to health impacts, as shown in the graph below. Unfortunately for all of us, the LDM is based on ludicrous simplifying assumptions. If we truly understood this, we would throw rocks at commentators who try to reassure us with comments like “less than one-tenth of the dose from a chest X-ray”.

The graphic is from a report for the National Academies, Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation: BEIR VII Phase 2. It was published in 2006. It looks very scientific, doesn’t it? Well, if you’ve ever been a science student working on a problem set at 2 a.m., figures like the graph above look very familiar. They all have the same legend, too. That legend says, “I Have No Friggin’ Idea, So Let’s Start With Something Really Simple”.

Don’t believe me? Well, this is from the caption to the figure:

The committee finds the linear no-threshold (LNT) model to be a computationally convenient starting point.

“Computationally convenient”, you will notice, does not mean “based on a scientific and thorough understanding of fundamental biology”.

There are actually at least two assumptions in this model. The first is not even hidden, but it’s so widely accepted that it’s very difficult to see it. Why is the absorbed energy (measured in Joules/kilogram), or dose, the appropriate metric to employ as the independent variable? It isn’t at all clear that this should be the case. I believe that the origin of this idea must be the Nobel Prize-winning work on X-ray mutagenesis by H.J. Muller, but there are two problems with its application.

1.A. Muller identified a clear correlation between dose of ionizing X-ray radiation and lethal mutation. He published his results in a famous paper titled “The Problem of Genetic Modification”. It escapes me, however, why anyone would assume that the pathway identified by Muller would be the ONLY means by which radiation can induce cancer. Yet this is certainly an assumption upon which the model relies. If we knew enough about cancer to know whether this assumption is justified, we would have cured cancer by now.

1.B. Cancer caused by radioactive fallout encompasses a range of chemical (strontium accumulates in bone, iodine in the thyroid, etc.) and radio- (alpha, beta, and gamma emitters, in addition to neutrons and fission products, all with a broad continuum of energies) activity. Lumping them all together into an “effective dose” using relative weights for different isotopes is what engineers refer to as a “kluge”. (This is a bit unfair to the cited BEIR VII report, which examines only gamma and X-rays. But the models cited are in fact applied to all forms of radiation, which I find hard to justify in general.)

I am actually sympathetic to the dose assumption. For one thing, I like the physics. If you’re trained in the field, then it’s sensible to think in terms of mass attenuation coefficients, linear energy transfer, cascades, and such things. But you should note that calculation of quantities such as these refer to model biological systems which are inanimate. This sounds complicated, but all it means is that dose calculations treat living beings as though they were not alive.

For another thing, I agree that, in the limit of very long time scales and even distribution of radioactive contaminants in the environment (unfortunately, along with millions of deaths), dose would be an excellent proxy for the variables which really determine the health outcomes for human beings. However, we don’t live in the long term, and radioactive contaminants are locally concentrated rather than globally dispersed. So the model doesn’t fit the real-world situation well.

On the other hand, dose works quite well to determine deaths and illness from high exposure levels – which was the primary concern of the original workers in the field. This brings us around to the second assumption.

The line in the figure above is extrapolated downward from high doses, where it agrees well with empirical data, to low doses, where it is very hard to get empirical data. The BEIR VII report explains well why this is so:

One challenge to understanding the health effects of radiation is that there is no general property that makes the effects of man-made radiation different from those of naturally occurring radiation. Still another difficulty is that of distinguishing cancers that occur because of radiation exposure from cancers that occur due to other causes. These facts are just some of the many that make it difficult to characterize the effects of ionizing radiation at low levels.

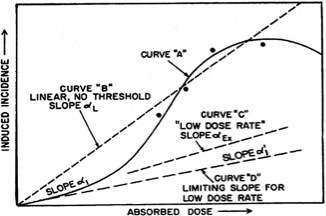

In any event, the graph below gives an idea of the conceptual framework behind the low-dose model. The figure makes it quite clear, I think, that there is no empirical evidence anchoring our belief about the existence or absence of low-dose health effects. (The only empirical data on the graph are the four points at high doses along Curve “A”.) The idea that lower absorbed doses must correlate to reduced adverse health effects therefore represents the second assumption underlying the LNT model.

The idea that we can simply extrapolate acute dose effects down to low doses is a very significant assumption. It certainly merits at least a cursory examination – which is what the BEIR VII report gives it:

Why Has the Committee Not Accepted the View That Low Doses Are Substantially More Harmful Than Estimated by the Linear No-Threshold Model?Some of the materials the committee reviewed included arguments that low doses of radiation are more harmful than a LNT model of effects would suggest. The BEIR VII committee has concluded that radiation health effects research, taken as a whole, does not support this view. In essence, the committee concludes that the higher the dose, the greater is the risk; the lower the dose, the lower is the likelihood of harm to human health. There are several intuitive ways to think about the reasons for this conclusion. First, any single track of ionizing radiation has the potential to cause cellular damage. However, if only one ionizing particle passes through a cell’s DNA, the chances of damage to the cell’s DNA are proportionately lower than if there are 10, 100, or 1000 such ionizing particles passing through it. There is no reason to expect a greater effect at lower doses from the physical interaction of the radiation with the cell’s DNA. [underlining mine]

This explanation sounds so obvious that it’s actually hard to open up your mind and question it. However, it is seriously, seriously flawed, and for an interesting reason. The BEIR VII explanation is wrong, in part, because cells can repair themselves – or “choose” not to. Therefore, while chromosomal damage does follow a linear dose dependence - as described - there are cellular feedbacks resulting from that damage which are highly non-linear with respect to dose. (Non-science translation: irradiated cells can respond in ways which are not strictly proportional to the dose.)

This conclusion is very surprising, since we’re encouraged to consider the idea that cells can repair radiation damage as evidence that low levels of radiation are not a significant danger. I do not think that this is necessarily true. The cell is a complex, rather autonomous entity; for instance, we understand that it is possible for the cellular machinery to run amok. (Our word for this situation is “cancer”.) Cellular regulatory mechanisms, when confronted with radiation damage, face at least two options:

1. If the damage is severe, the cell can undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis). In this case, the cell is disassembled, with the waste products absorbed by neighboring cells.

2. If the damage is less severe, the cell can attempt to repair the chromosomal injury caused by ionizing radiation. Because DNA is a very complicated molecule and nature is messy, however, sometimes this repair process will result in genetic mutation and cancer.

Note carefully: since the cells with less damage are more likely to undergo self-repair, it’s plausible that lower doses might correspond with a higher cancer risk. Oh.

In case you like to skip to the end, and you arrived at this point the quick way, you can read this next paragraph and be just as smart as everybody who read straight through. Harvey Wasserman gets it right in his Buzzflash article, “Safe” Radiation is a Lethal Lie:

Science has never found such a "safe" threshold, and never will.

It’s an interesting question to think about how, over time, the justifying assumptions supporting the LNT model have been internalized by the scientific community, until we reach the point where they’re not only no longer questioned, they’re scarcely recognized. Unfortunately, the results for the rest of us are - quite frankly - terrifying.

— Aaron Datesman

Posted at April 4, 2011 07:17 PMNote carefully: since the cells with less damage are more likely to undergo self-repair, it’s plausible that lower doses might correspond with a higher cancer risk. Oh.

This is assuming that after it flubs self-repair, it is then unable to undergo apoptosis, or activate any one of the hundreds of other checks on the way to transforming into a cancerous cell. It remains much more likely that a cell with lots of broken machinery is going to be transformed (because some of that broken machinery will include the apoptotic programs) than a cell with only a modicum of damage. If that is the only assumption at work here, I'm not sure I buy it. Your point about different types of radiation having different biological impacts is a good one, but I'm not sure the argument that low doses could be more dangerous because of repair mechanisms holds any water for me.

Posted by: saurabh at April 4, 2011 08:10 PMInteresting thoughts. But since we are all exposed to low levels of natural radiation and don't tend to usually die from cancer till later in life, I don't plan to volunteer at Fukushima so that the high doses of radiation there will save me. On a similar point of GIGO science Aaron, you should read some of the medical literature on cancer risk from X-rays. Much of it tries to relate the exposure from a CT scan to what happended at Hiroshima. They basically just pull numbers out of the air.

Posted by: John at April 4, 2011 08:45 PMHmm, justifying assumptions internalized until no longer questioned and scarcely recognzed--it's hard to believe that could have to educated people!

Seriously, the same pattern with modifications exists among economists, lawyers, journalists, politicians, doctors, businessmen, etc. Cults aren't limited to the kooky. Just start recognizing and questioning the justifying assumptions in yours and you'll see.

Posted by: N E at April 4, 2011 08:57 PMMr. Aaron:

It is my experience that Americans (which is the only group I have experience with) who don't have a science degree have a false view of what science is and what it can do. My countrymen tend to think that science can provide exact answers with absolute certainty. This is far from the truth and science is generally good at pointing out what the limitations on certainty are and the statement of we have no good reason to believe this to be true but it's the best thing we know how to do so we're starting here, reveals the limitation in this case but people want to here absolute certainty on news reports to be comforted so that's what they get.

As N.E. points out the scientific community tends to reinforce this ignorance itself and as you point out there are vital elements of convention that go unquestioned within the scientific community but the problem is social. A better education system would help but I fear this ignorance will persist as long as we value the bottom line more then truth.

Mr. John, Ms. Saurbah, and others:

My response to Mr. Aaron's argument is to question the conventional wisdom. It is still my guess that lower levels of radiation exposure carry lower health risks but I am reminded that that is just a guess and that perhaps I should have less faith in my guess then I had before. It's valuable to do this as it is good to be reminded of my ignorance from time to time especially when such a horror is occurring.

Posted by: Benjamin Arthur Schwab at April 4, 2011 09:47 PMThat graph is based on only 4 points! And they manage to draw 4 curves!!! Is this some kind of a joke?

Posted by: bobs at April 4, 2011 10:15 PMWhat is "natural background radiation? Are WE talking before June 5, 1945 or after?

Posted by: Mike Meyer at April 4, 2011 11:49 PMThere is much more empirical evidence for the dose-effect hypothesis of ionizing radiation as a cause of cancer than you give credit to in this post.

For one thing, the graph you link is on page 44 of a 400 page book that has chapters on atomic bomb survivors, medical exposures, and occupational exposures, among others. The common theme is that the long term cancer risk to people exposed to low doses of radiation (whether at Hiroshima, in a CT scanner, or in a nuclear power plant) is either identical or only slightly elevated from that of people in matched cohorts who don't share those exposures (but are exposed to radiation in everyday life).

Your thesis "it’s plausible that lower doses might correspond with a higher cancer risk." runs against that evidence. If you're right, you'd have to expect a markedly higher risk of cancer in people who've had a single chest X-ray, for instance.

You're also making what I think is a faulty assumption about the degree of exposure (and thus damage) to individual cells by a given dose of ionizing radiation. Remember that doses are measured by tissue or whole body exposure, not cell by cell. Any radiation absorbed by a tissue is going to be distributed across thousands and millions of cells. Higher doses of radiation will affect more cells in a tissue than lower doses, and will thus actually produce a larger number of cells that receive a "low dose" (in the way that you imply might interfere with apoptosis) at the same time as a few cells are receiving a "high dose" (in a way that you imply might kill the cell without causing cancer).

As far as I understand the physics, the model you're sniping at is meant to describe the mechanism of the dose-response curve seen in the situations described later in the book. The dose-response curve seen in real life is the empirical evidence, not the model. You don't actually have to understand exactly how something causes cancer to decide whether it does or it doesn't. That's how medicine works: you don't have to understand the exact mechanism by which Vibrio cholerae causes cholera, nor where the bacteria are coming from, to figure out that removing the Broad Street pump handle will help stop the epidemic. And it so happens that we do have what seems like a decent model for why ionizing radiation causes cancer, based on damage to DNA and its repair mechanisms. So it's not like we're flying completely blind, as far as we can tell.

I think you're at the point where you're looking for some way in which low doses of radiation are much more harmful than is supported by the evidence. You can come up with theories for how the recorded dose might be misleading (and so people in a valley near TMI might have had a much higher exposure than most models suggest). Even if that's true, it runs against what you've posted here, which is to suggest that actual low doses are much more harmful than advertised (not that some apparent low doses are actually high doses).

If you're going to stick with "it’s plausible that lower doses might correspond with a higher cancer risk", you're the one who needs to come up with empirical evidence.

Another point: the buzzflash post you recommend completely fails to explain the age-based pattern of radiation effects.

X-rays are contraindicated in pregnancy (Harvey Wasserman's first point) because they hurt the fetus, not the mother. A dose of radiation that is considered acceptably low for an adult (the typical adult in the literature is a 30 year old, because any increased cancer risk may only appear gradually over decades) is not considered safe (ie, is not considered a "low dose") for an infant. That's why CT scans are not recommended for children, especially before age 5.

But saying that low doses (of the level that is considered safe for workers at a nuclear power plant, or for an adult who needs medical investigations with a CT scan, let alone at the much, much smaller doses that have been detected so far in North America from Fukishima) are unsafe for infants and children is not to say that they're unsafe for adults. Implying as Wasserman does that those situations are equivalent runs against the empirical evidence. And further implying that the US is being "assaulted by yet another radioactive death cloud" and that people should be taking potassium iodide (which carries its own health risks) is taking fear mongering to the point where it can cause actual harm.

Posted by: pmpm at April 5, 2011 01:10 AM"Science has never found such a "safe" threshold, and never will."

Sure it has. Want a hint? You're soaking in it.

Posted by: Dilapidus at April 5, 2011 01:53 AMI generally agree, pmpm, except with saying that "you'll probably die of something else first" is the same as "not unsafe".

Posted by: saurabh at April 5, 2011 04:39 AMUh oh, talk about those assumptions and the next thing you know you're a fearmongerer.

Posted by: N E at April 5, 2011 06:22 AM@Saurabh -

The point I'm trying to make is that the underlined sentence is wrong. If the interacting material is inanimate, sure - then lower doses must have lower effects. But the long-term biological effects of low levels of ionizing radiation are not due to damage from the physical interaction. They are due to the biological responses to the physical damage on the part of the organism, at the levels of single cells, groups of cells, and even up to the affected organ. This is an intensely non-linear system.

In my opinion, when a scientist says, "There are several intuitive ways to think about....,"it's like a tell in poker. It's very, very hard work to accept any information which doesn't fit within one's framework of intuition. Therefore, it's not surprising that the report finds little evidence of health effects from low levels of ionizing radiation. The tell indicates that that's the assumption the authors had about the topic when they started.

This doesn't indicate corruption or dishonesty. It just indicates that scientists are humans, too, working in a contested field with ambiguous data. In that setting, I think we all should take a really hard look at what the assumptions are. That is all.

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at April 5, 2011 01:55 PM@pmpm -

Thanks for the long comment. I agree with much of it, actually.

The post does not intend to make an outrageous statement ("Low levels of radiation are more dangerous than nuclear bombs!") because I accidentally learned about apoptosis a few years ago. (I'm not a biologist. This was news to me.) That would require extraordinary evidence, which I won't be providing and do not have. I made that statement to point out that the underlined sentence in the BEIR report was clearly wrong. And it is.

I'm trying to make a simpler point, actually. Maybe I should have been more explicit about it. It's this: when we're told that atmospheric concentrations of radiocesium of 0.02 pCi/m^3 are safe, what's the scientific basis for this statement?

Well, reading the BEIR VII report, the short answer is:

We have some data from atomic bomb survivors, who survived prompt gamma blasts.

We drew a line and extrapolated leftward.

We did some studies with X-rays on small groups of cells.

And, we did some modeling dealing with energy deposition in tissue.

The jump from this experimental evidence (based principally on X-ray effects and ignoring biological feedbacks in living organisms) to conclusions about long-term fallout safety is simply tremendous. There are huge assumptions and gaps in our knowledge all along the way.

I think that people should understand just how imperfect our knowledge is.

I appreciate the comment; thanks! AD

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at April 5, 2011 02:13 PMDilapidius -

Sure, I'm aware of background radiation levels. But are they safe? There's no counterfactual to test against.

In fact, background radiation levels have risen quite a bit since 1945. Cancer rates have, too.

I wonder what that could mean.

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at April 5, 2011 02:18 PM@pmpm -

One additional point. You wrote:

"That's how medicine works: you don't have to understand the exact mechanism..."

That's interesting. Maybe it's true for cholera. It's not true for radioactive fallout. In order to make accurate estimates for each of the following stages in succession:

concentration in atmosphere

accumulation in body

concentration in organ

cell dose

cancer risk

we'd have to know a damn lot about a whole cascade of biological mechanisms.

The idea that we understand enough to make decisions regarding safe/unsafe is just damn hubris. All we know is that it isn't dangerous enough to kill us all immediately. The rest is speculation with just a thin veneer of science.

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at April 5, 2011 02:24 PMThat was a brilliant post. For those of you who are not engineers--you really have no idea how much of our technological society is based upon a series of convenient assumptions. Like Aaron said, it is a beautiful application of human intellect when it works, but often-times it gives us immensely false confidence in our knowledge. I think that central point got a little lost in some of the other comments. Mechanical engineering--which holds up the world and has given us industrial civilization, essentially--recently discovered that one of it's most basic principles (basically, bend some things hard enough and they deform, not hard enough at they bounce back) could be wrong, or over-simplified.

Posted by: Gordon at April 5, 2011 02:27 PMThe point I'm trying to make is that the underlined sentence is wrong.

No, the underlined sentence is correct (but incomplete) because it doesn't go into the effects of apoptosis and cell repair at all: it simply says that at lower doses there is a lower likelihood of "physical interaction of the radiation with the cell’s DNA".

In fact, background radiation levels have risen quite a bit since 1945. Cancer rates have, too. I wonder what that could mean.

Could that mean that health risk tends to increase with increasing levels of radiation? Or would that be improperly assuming a linear model?

Posted by: t.m. at April 6, 2011 05:47 AMit simply says that at lower doses there is a lower likelihood of "physical interaction of the radiation with the cell’s DNA".

No, that sentence says no such thing. It says:

'There is no reason to expect a greater effect at lower doses from the physical interaction of the radiation with the cell’s DNA.'

Where it's wrong is in the 'There is no reason to expect' bit.

Posted by: NomadUK at April 6, 2011 07:20 AMt.m. -

Doses are linear; biological effects are not. The principal problem here is that cell vs. organism and prompt vs. long-term effects are all rolled up in one package. That's part of the reason why the model stinks. What's worse, though, is that there's zero biology in it.

Otherwise, NomadUK made the correct response above, so I don't have more to add.

I generally agree, pmpm, except with saying that "you'll probably die of something else first" is the same as "not unsafe".

--It's the same as saying it's impossible to prove that it's unsafe. Sickness and death are universal, sooner or later. To show that something is harmful you have to show that exposure to it produces more sickness and/or death than whatever baseline would otherwise be expected (usually comparing to a matched cohort lacking that exposure).

"That's how medicine works: you don't have to understand the exact mechanism..."

That's interesting. Maybe it's true for cholera. It's not true for radioactive fallout. In order to make accurate estimates for each of the following stages in succession:

The point I'm making isn't about mechanisms, it's about epidemiology.

If low doses of radiation are somehow more harmful than higher doses, whatever the mechanism, you would see the effects of that harm. People with that low level of exposure would be developing cancer at a (statistically significantly) higher rate than those without it, or than those with a higher level of exposure.

In the absence of evidence of harm, different models of how low dose radiation might conceivably be harmful are not especially relevant.

In my opinion, when a scientist says, "There are several intuitive ways to think about....," it's like a tell in poker. It's very, very hard work to accept any information which doesn't fit within one's framework of intuition. Therefore, it's not surprising that the report finds little evidence of health effects from low levels of ionizing radiation. The tell indicates that that's the assumption the authors had about the topic when they started.

In my experience, whenever someone starts talking about non-linear effects, it's like a tell in poker. It shows that there's not much evidence for a connection that's being asserted.

Of course biology is full of non-linear effects, but that doesn't mean that the link between say smoking and lung cancer depends on handwaving and vague ideas about how tar and other inhaled pollutants trigger neoplastic changes. You count the people who smoke and the people who don't, match them up as best as you can, and then track the cancers they develop and see if they differ significantly. You can do that even if you think cigarettes are harmful because they release a demon miasma, or even if you think cancer is triggered by psychological factors of suppressed rage. It doesn't really matter why, you just know that smokers get cancer.

One more time, the reason why the commission doesn't find much evidence of harm from low doses of radiation is not because they're a bunch of blinkered fools who are depending on a faulty model to tell them what to think, but because in the real world, lots and lots of people have received low doses of radiation in various contexts and there's little or no evidence that they've suffered harm from it, either in the short or long term.

And again, this whole line of argument is completely antithetical to everything else you've written about TMI and nuclear power, which is that doses were much higher than advertised.

Posted by: pmpm at April 6, 2011 07:57 PMMx. pmpm, Mr. Aaron:

I think the two of you may be talking across each other and not at each other. It seams to me that you are both arguing different points, both of which I think are true and quite full and fascinating in an of themselves, but while the points can in fact be consistent with each other they may not have been put together in a way in which that is obvious.

From what I gather, the two statements are science doesn't know for sure what the effects of low doses of radiation are on the adult human body and a lack of knowledge shouldn't require action assuming the worst possibility.

I believe a claim that science and medicine don't know the probabilities for health changes when humans are exposed to low doses of radiation. Trying to do a study on the effect of low doses of radiation on human bodies thirty to fifty years after exposed seams imposable to me at present. I would also make the same claim for a study on subjects exposed to low doses of cigarette smoke. I would think that there would exist to many other factors to normalize for that would make a study unfeasible. It is true that background radiation rates have risen as well as cancer rates but so have certain other pollutants, the ability to detect cancer, telecommunication usage, and a hole assortment of other things. To recognize ignorance is important. Failure to find evidence when evidence would be beyond the ability to find is not a refutation of a possibility either.

As I make the claim that it is irresponsible to make a decision assuming the best possible outcome is going to happen, I would also make the claim that making decisions assuming the worst possible outcome is going to happen could also be irresponsible. Medical screening subjects patients to low doses of radiation frequently. Would it be responsible to stop these screenings because there is ignorance over how damaging the low doses might be and as far as we know, low doses might be quite deadly? I would say no, it wouldn't be responsible as that possibility is only a possibility and the screenings do have some demonstrable positive impact on health, both short term and long term.

Making decisions with the knowledge of ignorance is a non-trivial skill to learn and to implement but it is definitely possible. The issue of nuclear power generation and radiation risks is a complicated one as are most issues. It's not fear mongering to point out ignorance and unintentional or intentional deception, nor is pointing out a possibility an endorsement of that possibility. It seams to me like both of you are arguing that the other should be on his or her toes and I think both of you are. You're both being skeptical in the correct nature of scientists, but like all humans you are both prone to misscommunication sometimes.

I expect that the nuclear power industry at-large and public policy officials at-large overstate the safety of nuclear power. It is also my knowledge that American society deals with science poorly and the media will overstate the certainty of what officials pronounce and that the American public, by and large, expect that from science. Pointing out that things aren't as rosy as common knowledge and even intuition may suggest is valuable and a message that needs to be heard. Pointing out that this doesn't mean that the opposite bleak situation is the case is also a valuable task. I think the two of you would agree if you approach the situation not as people who need to prove each other wrong but actually address what the other is trying to say. It could also be that I misunderstand what the two of you are trying to say and everything I've said in this comment is inappropriate but that's the nature of human communication. As valuable as it is, it is inexact and will always lead to some confusion even when it eliminates more.

Posted by: Benjamin Arthur Schwab at April 6, 2011 09:27 PM@pmpm -

Well, here I think you've made a big mistake. Let's talk Chernobyl instead of TMI, because in that case everyone accepts that there was an enormous release of activity. The release was so large, in fact, that fallout from Chernobyl blankets the entire northern hemisphere.

Does this mean that the doses were large?

No, the activity was spread out over a vast area of land. Many, many people received small, long-term doses as a result of the Chernobyl disaster.

Maybe those low doses are totally safe. But the NYAS report on Chernobyl (the one based upon 5000 Russian studies) indicates that 137,000 deaths resulted from those low doses - in North America alone. If this is "little or no evidence", then BAS is right, and we are talking past one another.

I trained as an engineer and, if I could choose just one way to make the world a better place, I would choose to forbid any engineer from engaging in work in the fields of health, ecology, agriculture, or environmental science. Their brains are ruined for it by their reductionist training.

Unfortunately, the signs of models built by engineers are all over that BEIR report. This should make us all very worried.

Posted by: Aaron Datesman at April 6, 2011 10:43 PM@ Aaron:

I haven't read the NYAS paper and can't access it from home.

The value of the evidence it provides would rest on the quality of the epidemiology by which it came up with that statistic. 137K excess cancer deaths in North America is several orders of magnitude higher than any previous estimate. I don't know how they derived that figure, nor what controls they used. Controls might be hard to find, if doses were more uniform across North America than in areas closer to the origin of the fallout.

Perhaps you could do a post comparing and contrasting the methods and results used in the NYAS paper on Chernobyl with the studies on atomic bomb survivors, etc.

Still, Chernobyl is again the OPPOSITE of the point you are making in this post, which is that "it’s plausible that lower doses [of radiation] might correspond with a higher cancer risk" -- unless the incidence of Chernobyl-attributed cancer is higher in people who were less exposed (say, in North America) than more exposed (say, in Ukraine).

You still can't point to an example where lower dose radiation has been shown to be more harmful than higher dose (not just harmful in and of itself, but more harmful than a higher dose). And until you do, the argument/insinuation in this post is more homeopathy than engineering, sorry. You don't need this kind of "God of the gaps" argument to show that nuclear fallout is a Bad Thing or that nuclear power is Dangerous (both obviously true).

@ BA Schwab

From what I gather, the two statements are science doesn't know for sure what the effects of low doses of radiation are on the adult human body and a lack of knowledge shouldn't require action assuming the worst possibility.

It's not so much that there is a lack of knowledge, but that the knowledge we have so far (epidemiological studies from Hiroshima, medical imaging, etc) fails to show a causal relationship between exposure to low doses of radiation and excess cancer deaths. If you want to challenge that statement, you have to either undercut the validity of the existing data (by showing that those studies were poorly done, or that the data are fraudulent because it's all part of a massive cover-up, or whatever), or provide enough well-supported competing data to outweigh it. Maybe the NYAS study is a first step there, I don't know.

Posted by: pmpm at April 7, 2011 12:37 AMMx. pmpm:

"It's not so much that there is a lack of knowledge, but that the knowledge we have so far (epidemiological studies from Hiroshima, medical imaging, etc) fails to show a causal relationship between exposure to low doses of radiation and excess cancer deaths."

I can believe that statement but a lack of evidence supporting a possibility is different then evidence that the possibility is false. If one is to make the claim that low doses of radiation do not lead to excess cancer deaths then evidence actively supporting the claim needs to be found. I suspect that a study to verify that statement is infeasible at-least at this time.

Mr. Aaron:

"I trained as an engineer and, if I could choose just one way to make the world a better place, I would choose to forbid any engineer from engaging in work in the fields of health, ecology, agriculture, or environmental science. Their brains are ruined for it by their reductionist training."

In my experience every field is frightening if one knows much about it. Research doctors have their own scary norms. In short there are problems everywhere one looks and I am actually comforted by diversity in educational backgrounds on the same working group or team and favor cross discipline training and employment. With engineers and doctors working on the same study, both have the opportunity to pick up on the negligence of the other.

Posted by: Benjamin Arthur Schwab at April 7, 2011 05:42 PMBenjamin Arthur Schwab

"In my experience every field is frightening if one knows much about it."

Yep.

My imitation of Tom Friedman again

During the 1990s, I rode around in two separate cabs driven by Ukrainian emigre taxi drivers who said they had had been very close to Cherynobyl during the tragedy. Neither of them had a hair on his head. This seemed noteworthy to me, and in honor of mistah charley, that' my misleading Friedmanesque taxi cab driver topical anecdote for the day.

As far as what pmpm states in refuting the main argument(s) of the OP, a Dr John Goffman, who was one of the leading experts on Atomic Energy, radiation etc, did indeed say that cancer rates increase in direct proportion to the X Rays given.

He had a lot of accumulated data that showed how much cancer rates accelerated inside a given population once X Ray machines were available to the population.

Dr Goffman died several years ago.

Oh and for many many reasons, he was really unpopular with those in our government and universities who wanted radiation technology used for everything from treating cancer patients with radiation to setting up a huge infra structure of nuke reactors.

Posted by: Schmoo at April 8, 2011 04:34 PMpmpm: In my experience, whenever someone starts talking about non-linear effects, it's like a tell in poker.

Exactly...

NomadUK: Where it's wrong is in the 'There is no reason to expect' bit.

It's only wrong if you ignore the "from the physical interaction" qualification. Before you can get to the biological effects of radiation, it seems appropriate to address how much radiation is physically in the position to cause such effects.

Aaron: The principal problem here is that cell vs. organism and prompt vs. long-term effects are all rolled up in one package.

The same thing might be said of your argument that 'since the cells with less damage are more likely to undergo self-repair, it’s plausible that lower doses might correspond with a higher cancer risk'. That might be true of an individual cell, but if an organism is bombarded with increasing levels of radiation, the number of cells that get hit and survive will increase alongside the number of cells that go into apoptosis (unless the radiation is at immediately lethal levels).

And you missed the point of my question - if you make the (plausible) claim that increased background radiation or x-rays or emissions from nuclear plants tends to increase cancer deaths, you are assuming that a simple model (be it linear, logarithmic, or whatever) can be used to describe the relationship between the variables despite the biological complications (at least on a coarse, population level). You are using dose as "an excellent proxy for the variables which really determine the health outcomes for human beings"!

Posted by: t.m. at April 8, 2011 06:38 PMpmpm: In my experience, whenever someone starts talking about non-linear effects, it's like a tell in poker.

Exactly...

NomadUK: Where it's wrong is in the 'There is no reason to expect' bit.

It's only wrong if you ignore the "from the physical interaction" qualification. Before you can get to the biological effects of radiation, it seems appropriate to address how much radiation is physically in the position to cause such effects.

Aaron: The principal problem here is that cell vs. organism and prompt vs. long-term effects are all rolled up in one package.

The same thing might be said of your argument that 'since the cells with less damage are more likely to undergo self-repair, it’s plausible that lower doses might correspond with a higher cancer risk'. That might be true of an individual cell, but if an organism is bombarded with increasing levels of radiation, the number of cells that get hit and survive will increase alongside the number of cells that go into apoptosis (unless the radiation is at immediately lethal levels).

And you missed the point of my question - if you make the (plausible) claim that increased background radiation or x-rays or emissions from nuclear plants tends to increase cancer deaths, you are assuming that a simple model (be it linear, logarithmic, or whatever) can be used to describe the relationship between the variables despite the biological complications (at least on a coarse, population level). You are using dose as "an excellent proxy for the variables which really determine the health outcomes for human beings"!

Posted by: t.m. at April 8, 2011 06:39 PMSorry about the double post. And one more reason why focusing on apoptosis may be misleading: the development of cancer usually requires multiple mutations in a cell.

Posted by: t.m. at April 8, 2011 07:09 PM